Feet and footwear

James Earls discusses the impact of wearing shoes on feet.

A recent study found that walking speeds in 85% of elderly men and 93% of elderly women have reduced so much that they can no longer cross the road at speeds considered safe1. Although this study was only performed in England, the results are in keeping with studies performed in Ireland, South Africa, Spain and the United States. It is hard not to see how this may relate to other statistics that show that 85% of the population is wearing incorrectly sized shoes2, that 87% of older adults have some form of foot dysfunction3, with up to 74% having a hallux valgus, and one in 40 people over the age of 50 suffer with a hallux rigidus4.

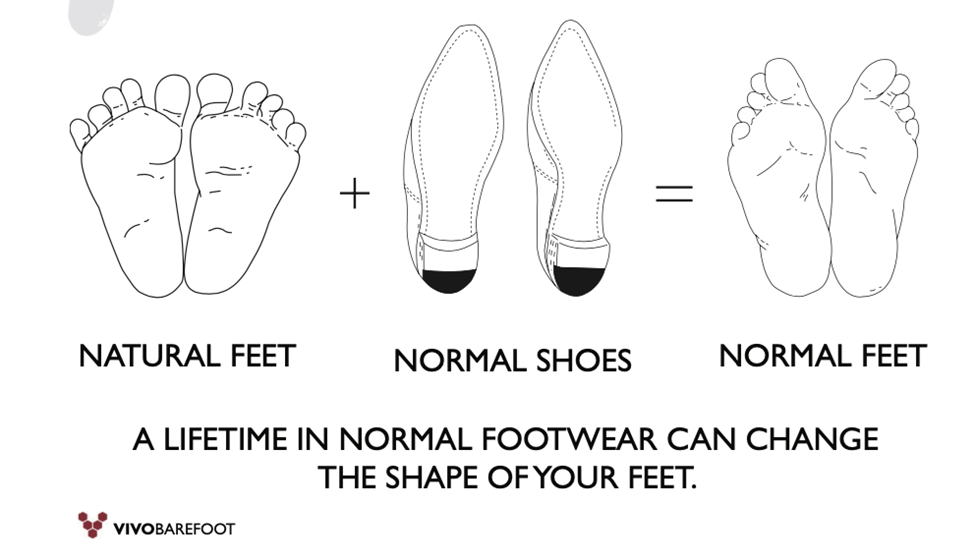

In each category of dysfunction, female feet are worse than men’s, and I am sure few people would contest that women’s footwear is less foot-shaped than men’s (Figure 1). Women’s shoes also tend to have higher heels, which places extra stress on the metatarsal heads, realigns the ankle to a plantar flexed position and, over time, can shorten the gastrocnemius and stiffen the Achilles’ tendon3.

Each misalignment and every reduced range of motion will affect bone and soft tissue function. There are many benefits to tensioning collagenous tissues during natural movement, and joint and soft tissue alignments overlap to ensure the system flows with ease. Changing toe alignment or artificially reducing the range of joint motion robs the system of momentum and the force enhancements from pretensioning.

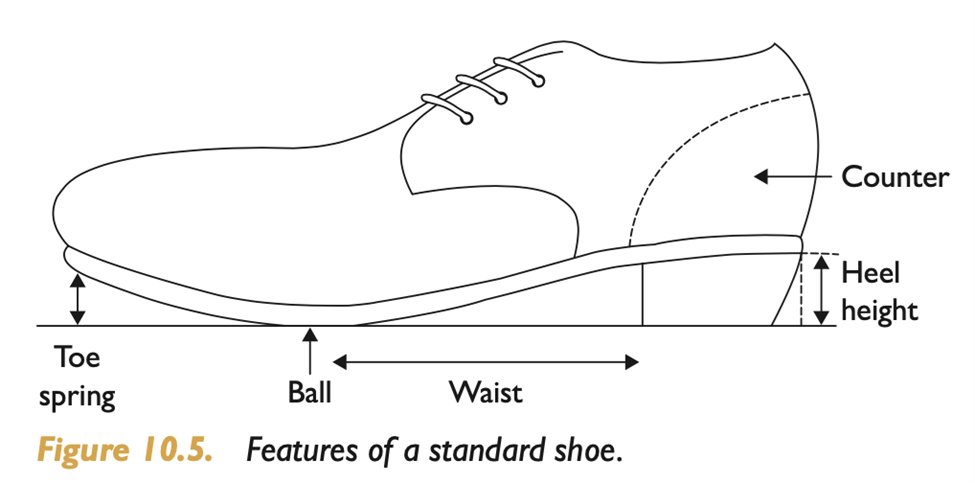

Shoe design can affect the pretensioning of the plantar tissues in many ways. The most obvious is the toe spring, the upward curve of the sole beyond the ball, which is often used by manufacturers to compensate for the stiffness of the sole (Figure 2). If the material used for the sole of the shoe is difficult to bend, it will stop the metatarsal joints from extending. Shoe manufacturers compensate for this with an in-built toe spring to exaggerate the ball of the shoe.

The effect on the foot is to reduce or remove toe extension and, by doing so, reduce the amount of work performed by the flexor tissues. It should be no surprise that outsourcing the work of the foot to the shoe causes the foot to weaken, as the muscles are no longer being used for deceleration and control. A study by Sichting et al5 found that toe springs reduce the workload and decrease the stiffness of the medial longitudinal arch, an effect they warn may have long-term consequences for foot health, as the intrinsic muscles become weaker over time due to underuse.

However, we need to be aware to not fall foul of the appeal to nature argument. It is always important to read research with a critical eye as we can learn a clinical lesson from the study. Sichting and colleagues show that toe springs divert work from the plantar tissues and into the form of the shoe, which is not a good thing for a healthy foot. It is a totally different story if the foot is already challenged. In cases of plantar heel pain, plantar fascia pain or metatarsalgia, toe springs could be a clinically useful device for the temporary unloading of tissues that may be under stress. In cases of plantar heel pain, plantar fascia pain or metatarsalgia, toe springs could be used to off-load the tissues and give them time to heal without requiring the client to completely rest.

A comprehensive review of related literature by Holowka and Lieberman6 showed that habitually shod populations generally had weaker feet and recorded lower height and stiffness of the medial longitudinal arch than habitually unshod populations. In their study, Holowka and Lieberman showed that wearing minimalist shoes could significantly increase the cross-sectional area of abductor hallucis and, to a lesser extent, the cross-sectional areas of abductor digiti minimi and flexor digitorum brevis. Minimalist shoes allow the foot to spread and the toes to extend, so it should be no surprise that letting the foot follow its natural function makes the associated muscles work a little harder. These intrinsic muscles form part of the ‘foot core system’ proposed by McKeon et al7 and, like any ‘core’, the muscles benefit from working out. Conveniently, we do not need to go to the gym to exercise the feet, we could be working them with every step – if we are wearing the right shoes!

As part of their construction, minimalist shoes have flexible and thin soles that not only allow the plantar tissues to engage but also enhance sensory stimulation. The foot can feel the surface more clearly and, by stiffening the tissues, the mechanoreceptors receive appropriate information regarding the pressure, shear and stretch that is unavailable to them in a stiff, cramped shoe. Once again, though, modern shoes can offer something to the pathological foot. As the major function of shoes is to protect the foot, we must consider those with challenged tissues. Both peripheral vascular and neurological deficits can increase sensitivity or, dangerously, decrease it to the extent that the client is unaware of any tissue damage. All too commonly in cases of diabetes, injury to the foot leads to complications that require amputation. Ensuring properly fitted shoes are worn can reduce injuries and should form part of any quality care package.

In less serious conditions, such as plantar fascia conditions, a shock-absorbing sole can temporarily reduce strain on the tissue and speed recovery. In fact, any condition that has challenged the soft tissues can benefit from some rest and recovery time and the support given by a shoe. For example, reduced fat pad coverage can be compensated for with an absorbent heel as the calcaneal fat pads deform up to 60% with minimalist shoes, but only 35% in conventional running shoes.

Figure 1: We are shaped by our environment. Every trainer knows the benefit of correct form and the dangers of incorrect mechanics but, yet, we still allow ourselves and our clients to perform tasks in shoes that alter the shape of our feet. We might feel fine in the short term but what are the long-term effects on feet that live in a shoe-shaped environment? (Image courtesy of Vivobarefoot)

Figure 2: Just as we need to learn human anatomy to understand how the body functions, knowing the anatomy of a shoe can give us a better appreciation of how footwear can affect function.

References

- Asher L, Aresu M, Falaschetti E, Mindell J (2012), Most older pedestrians are unable to cross the road in time: a cross-sectional study, Age and Ageing, 41(5): 690-94.

- Tyrrell J, Jones S, Beaumont R, Astley C, Lovell R, Yaghootkar H, Tuke,M, Ruth K, Freathy R, Hirschhorn J, Wood A, Murray A, Weedon M, Frayling T (2016), Height, body mass index, and socioeconomic status: mendelian randomisation study in UK biobank, British Medical Journal, 352: i582.

- Franklin S, Grey M, Heneghan N, Bowen L, Li F-X (2015), Barefoot vs common footwear: a systematic review of the kinematic, kinetic and muscle activity differences during walking, Gait & Posture, 42(3): 230-39.

- Rodríguez-Sanz D, Tovaruela-Carrión N, López-López D, Palomo-López P, Romero-Morales C, Navarro-Flores E, Calvo-Lobo C (2018), ‘Foot disorders in the elderly: a mini-review,’ Disease–a–Month, 64(3): 64-91.

- Sichting F, Holowka N, Ebrecht F, Lieberman D (2020), ‘Evolutionary anatomy of the plantar aponeurosis in primates, including humans,’ Journal of Anatomy, 237(1): 85-104.

- Holowka N, Wallace I, Lieberman D (2018), ‘Foot strength and stiffness are related to footwear use in a comparison of minimally- vs. conventionally-shod populations,’ Scientific Reports, 8(1): 3,679.

- McKeon P, Hertel J, Bramble D, Davis I (2014), ‘The foot core system: a new paradigm for understanding intrinsic foot muscle function,’ British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(5): 290.

Many thanks to James Earls for offering all of the FitPro community a discount to the Feet, Fascia & Function Summit on 20 November 2021. You can attend the summit for just £99 (currently £125, soon to go to £135!).

The eventbrite link is: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/feet-fascia-function-summit-2021-tickets-160522279459

Use the following discount code: FitProDiscount

Author Bio:

Based in London, James Earls is a writer, lecturer and bodyworker, specialising in Myofascial Release and Comparative Anatomy. He is a graduate of the Gray Institute’s GIFT training and recently completed an MSc in Human Anatomy and Evolution. James has authored two books – Fascial Release for Structural Balance and Born to Walk, and, in between walks and workouts, is currently working on a third.