Justin Price details how scar tissue is formed, how it affects pain and performance, and some simple and effective techniques to help you and your clients mitigate its negative physical effects on the body.

Many people have scars as a result of accidents, injuries and surgeries. While scar tissue is extremely helpful at repairing cells quickly to prevent further damage and/or injury, the characteristics of scars and their presence in the body can restrict and inhibit movement. This can lead to myofascial pain and musculoskeletal imbalances and, ultimately, can impede athletic performance.

What is scar tissue?

Scar tissue is made from the same matter as every other soft tissue in the body (i.e., collagen). Scars form in the body to replace injured tissue any time a soft tissue structure, such as the skin, muscles, fascia, ligaments and/or tendons, has been damaged. When healthy tissue is injured, the body responds to the problem by first stopping the bleeding (with a blood clot). It then starts producing collagen excessively to heal the wound as fast as possible.1 During this rapid repair process, the body prioritises mending the injury ahead of making sure the newly formed collagen fibres are neatly lined up and organised in the same fashion as the original tissue before it was damaged. As a result of the process, scar tissue is not as flexible as healthy tissue, not structured in the same way and does not have a normal blood supply, sweat glands or hair.1 Therefore, while scar tissue is extremely effective at helping to protect and repair, the functionality and elasticity of it is different from the surrounding tissue.

Scar tissue and its effect on pain and performance

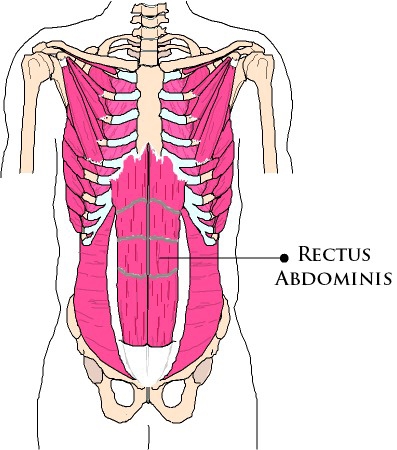

Fitness professionals are experts in muscles and movement. They understand that muscle fibres are striated in the direction of force that they generate.2 However, since the configuration of scar tissue is not the same as the surrounding muscle fibres, it can alter the way these structures work. For example, the muscle fibres of the rectus abdominis are striated in a longitudinal fashion running up and down the torso (see Figure 1).

They are organised in this direction because this muscle helps flex the trunk during movements such as abdominal crunches and lifting the spine up to get out of bed. Similarly, these muscle fibres also need to lengthen to help slow down extension of the spine during movements such reaching over your head to wash your hair, arching your back to hit a volleyball spike or performing a tennis serve.

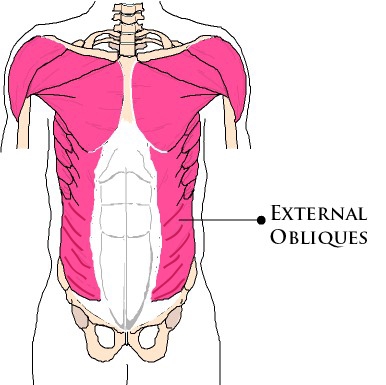

Alternatively, the external obliques wrap around the torso and the fibres are almost perpendicular in relation to the spine (see Figure 2).

They are striated as such because these muscles are primarily involved with rotation of the trunk. They help with movements such as swinging the arms when walking, the backswing and follow-through in golf, and reaching behind you to grab something out of the back seat in the car.2

Many people undergo surgeries in the abdominal region that require cutting through the rectus abdominis, external obliques and other muscle tissue and fascia of the abdominal wall (i.e., hysterectomies, gallbladder and appendix removal, hernia repairs, etc.). While these procedures may be life-saving and/or absolutely necessary, unfortunately they produce a lot of scar tissue that affects the function of both the rectus abdominis and external oblique muscles.3

There are many other commonplace surgeries that can also affect the way the body moves and functions. Hip replacement surgeries typically result in extensive scarring to the gluteal complex of muscles. The fibres of the gluteal muscles all run obliquely across the back of the hip and help to slow down both gravity and ground reaction forces to the lower back, sacroiliac joint, hip complex, pelvis, leg and knee. As such, when scarring compromises the integrity and function of these muscles, movements involving these joint structures can become dysfunctional and pain can result. Similarly, knee replacement surgery (another very common orthopedic procedure) causes scarring to the structures of the knee and affects the function of the quadriceps muscles (which run longitudinally from the front of the hip and pelvis down to the knee). The interconnected nature of the body via its fascial systems means that not only local joints are affected by scarring from these types of procedures, but so too is movement and performance of the body as a whole.4,5,6

Surgeries involving internal organs also produce scar tissue and visceral adhesions that can affect the ability of other structures in the body to function correctly. Since all organs have connections with other soft tissue structures and many have ligamentous attachments to the spine, scar tissue in or around organs can create pain, disease and widespread musculoskeletal dysfunction.3 For example, the gallbladder and bile duct are connected to the liver and pancreas. These, in turn, are fascially connected to the diaphragm, which is attached to the ribcage. A surgery to any of these three organs, therefore, produces scar tissue that can disrupt breathing and function of the ribcage. Needless to say, this can impede performance and cause many musculoskeletal imbalances.2

Ask clients about past injuries, surgeries and accidents

The majority of personal training clients have chronic or temporary injuries. However, these same clients want to improve their athletic performance and increase their functional abilities so they can engage in daily activities without pain.7 Therefore, it is highly recommended as part of your initial consultation and/or corrective exercise programming strategies that you ask clients about past injuries, surgeries and accidents. Doing so will enable you to ascertain information regarding the types and extent of scar tissue present in their body. If a client has extensive scar tissue or scarring in any major muscles of the body that seems to affect their ability to move correctly, you can talk with them about referrals to appropriate medical professionals/specialists and/or recommend strategies for treating scar tissue. Addressing issues related to scar tissue will ultimately help improve your clients’ functional capabilities and decrease their sensations of pain.5,6

Healing and treating scar tissue

If you have had an accident, injury and/or surgery, then the development of scar tissue is unavoidable. However, genetics and age also play a role in the development of scar tissue. As people age, it becomes more difficult for the body to generate new cells and scarring can happen more easily. Yet, no matter how extensive the scarring or the age of the patient/client, there are many techniques and strategies that can be used to decrease the build-up of scar tissue.

Protection of the wounded area

When tissues are injured, they must initially be protected from further harm. Depending on the severity and type of wound, bandages/dressings are recommended (as well as antibiotics in some cases) for maintaining cleanliness of the area and to prevent infection. Most wounds are best kept clean with a saline solution, as chemicals and other harsh soaps can dry out the skin, prevent healing and worsen scarring.

Nutrition

Vitamin C is used throughout the body for cell repair and is generally recommended to help the body recover from injury. Furthermore, a vitamin B complex may also help speed up the recovery process and promote healing.8 However, as with any nutritional advice you provide your clients, it is recommended that you consult with a licensed dietitian/nutritionist before making any nutritional suggestions to help diminish/treat scar tissue.

Massage

After a scar has healed initially, a person can increase flexibility in the scar tissue and surrounding tissue by massaging the area with a doctor/surgeon-recommended gel or ointment. As the scar heals further, self-myofascial release and/or trigger point therapy may be used to improve the elasticity of the surrounding myofascial structures, as well as bring new blood supply to the affected area. Always obtain medical clearance before employing any type of self-myofascial release or trigger point technique to ensure you do not re-injure the area.

Laser/light therapy

Many people are familiar with the use of laser treatment and dermabrasion to improve the surface of the skin and remove superficial scars. However, it has also been demonstrated that low-level laser therapy can improve cellular function and help with the treatment of deep scars. Moreover, the exposure to sunshine (and ultraviolet light) has also been shown to improve cellular function to damaged tissue and scars. However, it is important to consult with your (or your client’s) physician first to make sure the initial wound has completely healed before recommending exposure to sunlight, as that can make scarring worse in some cases.9

Vibration

The formation of scar tissue can sometimes affect the activation of a muscle or surrounding muscle groups by interfering with the neural pathways that activate those tissues. Recent research has demonstrated that, when high-frequency vibration is applied to adhesions, scar tissue and the surrounding muscle, nerves can be stimulated to help improve the function of muscle tissue that has been affected by the formation of scar tissue.10

Surgery

When scar tissue is severely limiting function of the body and/or causing pain, surgery is sometimes recommended to remove the build-up of the old scar tissue. However, this option is a last resort, as the simple act of cutting the old scar out produces a new scar, which is not guaranteed to be less mobile/supple than the old one.

Conclusion

While scars naturally heal and fade over time, their impact on your physical movement capabilities may remain. Recognising the far-reaching effects of scar tissue, identifying those areas of the body that are affected by it and applying appropriate strategies to treat scars can help you limit their potential to cause pain and dysfunction, and inhibit performance. Promoting effective healing of new wound sites and treating old scar tissue build-up are two ways to lessen the negative impact scar tissue has on the body. Remember to always check with your (or your client’s) doctor/surgeon before recommending any strategies or techniques that are beyond your scope of practice as a fitness professional/personal trainer.

Explore our sports massage therapist insurance and get covered today.

References

- Kraft J (2014), How to Heal Scar Tissue: How to Heal Your Own Scar Tissue and Get Rid of It!, Jonathan Kraft, CMT.

- Gray H (1995), Gray’s Anatomy, New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

- RolfIP (1989), Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well-Being (revised edition), Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

- Myers T (2001), Anatomy Trains. Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Price J (2010), The BioMechanics Method Corrective Exercise Educational Program (2nd Edition), The BioMechanics Press.

- Price J (2018), The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- IDEA (2013), IDEA Fitness Programs and Equipment Trends Report, IDEA Health & Fitness Association.

- Harker M (2005), Health and Healing, New Zealand: Wings of Waitaha Books.

- Doidge N (2015), The Brain’s Way of Healing: Remarkable Discoveries and Recoveries from the Frontiers of Neuroplasticity, Penguin, USA.

- Cochrane DJ (2011), The potential neural mechanisms of acute indirect vibration, Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 10: 19-30.