Does your work require you to work out with clients or run high-energy classes while you still train towards your own physical fitness goals? James Phillips, strength and conditioning coach at Pure Sports Medicine, gives you some pointers on how to look after yourself and, therefore, your job, clients and life.

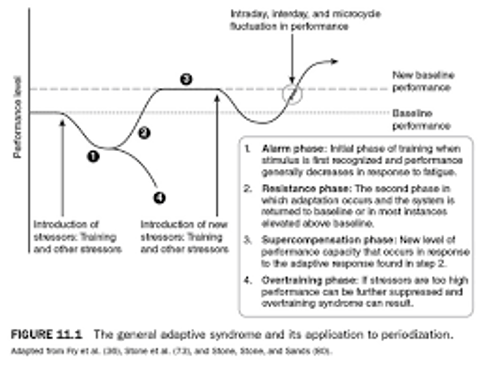

We all know that training regularly can hugely benefit our physical condition and psychological wellbeing. And, if we educate clients to train hard, then we certainly should educate them to recover hard. Using Han Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome theory, we adapt to the stress of a workout or training block through a period of relative rest to allow our bodies to reach a super-compensated physical level. This requires adequate length and quality of recovery from the stimulus. We can think of recovery in three different phases:

- Short-term recovery – between a set of repetitions

- Acute training recovery – following a singular training session

- Chronic training recovery – following an accumulation of training sessions (one week or month)

This theory can be applied to each type of recovery. The types of fatigue that will consequently affect what we are recovering from are different with each type of recovery.

This theory can be applied to each type of recovery. The types of fatigue that will consequently affect what we are recovering from are different with each type of recovery.

If recovery following stress or stimulus is insufficient, then our homeostasis has not returned to its original state (and certainly not a super-compensated state) and starts to overreach, which can lead to an overtrained state. There are many factors that could affect one’s ability to recover – here is a non-exhaustive list: sleep, hydration status, refuelling strategies, relative rest and stress.

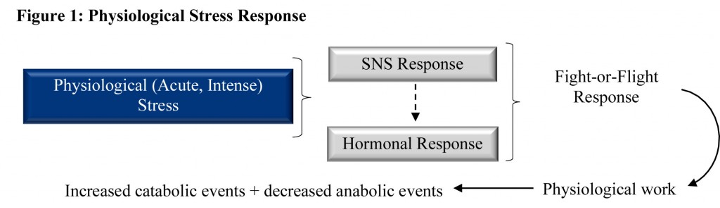

Stress is a general term used to describe a non-specific response to any stimulus that overcomes, or threatens to overcome, the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis. What’s important here is that the biological response to stress is the same, regardless of the stimulus.

Our biological stress response has two routes: neural and endocrine.

- Neural response is the fast, instantaneous reaction (e.g., pulling our hand away from a hot pan).

- Endocrine response is the slow-acting, gradual production or reduction of circulating hormones designed to create a long-lasting response.

But stress isn’t bad, right? Well, it’s how we perceive the stress that will impact on our mortality (“will it kill me?”). Skydiving could be viewed as a good way to die – others do it for fun on a regular basis. A high stressor for someone isn’t always a high stressor for all. Today’s stressors are much more subtle and lower in intensity but, if constantly exposed, this can accumulate (e.g., “my job certainly isn’t going to kill me …”).

But stress isn’t bad, right? Well, it’s how we perceive the stress that will impact on our mortality (“will it kill me?”). Skydiving could be viewed as a good way to die – others do it for fun on a regular basis. A high stressor for someone isn’t always a high stressor for all. Today’s stressors are much more subtle and lower in intensity but, if constantly exposed, this can accumulate (e.g., “my job certainly isn’t going to kill me …”).

During our fight or flight response, our body selectively inhibits certain systems to enhance another in order to provide necessary resources. For example, cortisol is THE stress hormone, released in response to stress. It has many benefits under acute responses to stress, such as:

- elevated heart rate

- helping to control the regulation of fat metabolism

- sparing liver glycogen

- increasing circulating blood glucose

- playing a role in our sleep-wake cycle

- regulating blood pressure.

But there are also consequences when we have elevated circulating levels of cortisol for consistent periods of time. The hormonal actions secreted to cause an effect are muted, impeded or even inhibited. Elevated levels of cortisol have consequences such as:

- inhibited human growth hormone secretion, which promotes fat utilisation, tissue growth and repair

- inhibited oestrogen secretion, decreasing libido and increasing fat storage

- inhibited testosterone secretion, decreasing muscle growth and increasing fat storage

- altering sensitivity to leptin and ghrelin, the hormones controlling hunger and appetite.

But what if your work requires high levels of exertion on a regular basis, you train on top of this because your work isn’t training, and you have multiple classes that require you to create an environment of high energy? You can quickly see how a fitness instructor, personal trainer or coach can accumulate stress both physiologically and psychologically. As a result, we fitness professionals really should practise what we preach when it comes to the advice we offer to our clients relating to recovery and make sure we give ourselves adequate time to recover – especially when our livelihoods often depend on us remaining active, particularly if we’re taking classes. The old adage of listening to your body can be an effective way of managing yourself, but it’s generally advisable to have at least one full rest day each week, combined with two or three lighter days interspersed with harder days. For example, if you’re taking multiple spin classes in one day, it’s a good idea to go easy in your own training that day. It’s also a good idea to use a day off as just that – have a relaxed day, avoid training and put your feet up where possible. You’ll then be able to look forward to a heavy training session feeling refreshed the following day, depending on what your schedule looks like.

For more advice on how to look after yourself, as well as what to do should injury strike, visit us at puresportsmed.com.

Author Bio:

James Phillips has been a Strength and Conditioning coach for over 10 years, developing his knowledge, experience and coaching eye within both the sporting world and private healthcare. He has a Master of Science (MSc) degree in Strength and Conditioning (2012) from Middlesex University and a Bachelor of Science degree (BSc) in Sport Science and Maths (2010) from Loughborough University.

He has previously worked in elite sport at Saracens Rugby Club, English Institute of Sport, and with British Fencing. He then turned his career towards private healthcare and has become specialised in end stage rehabilitation.

James’ is highly skilled in Force Plate testing for both injury rehabilitation and performance and is experienced in developing physical performance in the endurance athlete and in designing holistic training plans for the active individual.

Co-Founder of the course ‘The Complete ACL Journey’ alongside Andrew Goodall, James has become a leading expert in ACL end stage rehabilitation and return to performance. Rehabilitating a cohort of patients ranging from the conservative recreational athlete to the complex multi-ligament injury. Now awaiting a recent publication researching outcomes within ACL injury.